Protein secondary structure

In biochemistry and structural biology, secondary structure is the general three-dimensional form of local segments of biopolymers such as proteins and nucleic acids (DNA/RNA). It does not, however, describe specific atomic positions in three-dimensional space, which are considered to be tertiary structure.

Secondary structure can be formally defined by the hydrogen bonds of the biopolymer, as observed in an atomic-resolution structure. In proteins, the secondary structure is defined by the patterns of hydrogen bonds between backbone amide and carboxyl groups. In nucleic acids, the secondary structure is defined by the hydrogen bonding between the nitrogenous bases. The hydrogen bonding patterns may be significantly distorted, which makes an automatic determination of secondary structure difficult.

The secondary structure may be also defined based on the regular pattern of backbone dihedral angles in a particular region of the Ramachandran plot; thus, a segment of residues with such dihedral angles may be called a helix, regardless of whether it has the correct hydrogen bonds. The secondary structure may be also provided by crystallographers in the corresponding PDB file.

The rough secondary-structure content of a biopolymer (e.g., "this protein is 40% α-helix and 20% β-sheet.") can often be estimated spectroscopically. For proteins, a common method is far-ultraviolet (far-UV, 170-250 nm) circular dichroism. A pronounced double minimum at 208 and 222 nm indicate α-helical structure, whereas a single minimum at 204 nm or 217 nm reflects random-coil or β-sheet structure, respectively. A less common method is infrared spectroscopy, which detects differences in the bond oscillations of amide groups due to hydrogen-bonding. Finally, secondary-structure contents may be estimated accurately using the chemical shifts of an unassigned NMR spectrum.

Secondary structure was introduced by Kaj Ulrik Linderstrøm-Lang at Stanford in 1952.

Contents |

Protein

Secondary structure in proteins consists of local inter-residue interactions mediated by hydrogen bonds, or not. The most common secondary structures are alpha helices and beta sheets. Other helices, such as the 310 helix and π helix, are calculated to have energetically favorable hydrogen-bonding patterns but are rarely if ever observed in natural proteins except at the ends of α helices due to unfavorable backbone packing in the center of the helix. Other extended structures such as the polyproline helix and alpha sheet are rare in native state proteins but are often hypothesized as important protein folding intermediates. Tight turns and loose, flexible loops link the more "regular" secondary structure elements. The random coil is not a true secondary structure, but is the class of conformations that indicate an absence of regular secondary structure.

Amino acids vary in their ability to form the various secondary structure elements. Proline and glycine are sometimes known as "helix breakers" because they disrupt the regularity of the α helical backbone conformation; however, both have unusual conformational abilities and are commonly found in turns. Amino acids that prefer to adopt helical conformations in proteins include methionine, alanine, leucine, glutamate and lysine ("MALEK" in amino-acid 1-letter codes); by contrast, the large aromatic residues (tryptophan, tyrosine and phenylalanine) and  -branched amino acids (isoleucine, valine, and threonine) prefer to adopt β-strand conformations. However, these preferences are not strong enough to produce a reliable method of predicting secondary structure from sequence alone.

-branched amino acids (isoleucine, valine, and threonine) prefer to adopt β-strand conformations. However, these preferences are not strong enough to produce a reliable method of predicting secondary structure from sequence alone.

There are several methods for defining protein secondary structure (e.g. DEFINE,[1] DSSP,[2] STRIDE (protein)[3]).

| Geometry attribute | α-helix | 310 helix | π-helix |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residues per turn | 3.6 | 3.0 | 4.4 |

| Translation per residue | 1.5 Å (0.15 nm) | 2.0 Å (0.20 nm) | 1.1 Å (0.11 nm) |

| Radius of helix | 2.3 Å (0.23 nm) | 1.9 Å (0.19 nm) | 2.8 Å (0.28 nm) |

| Pitch | 5.4 Å (0.54 nm) | 6.0 Å (0.60 nm) | 4.8 Å (0.48 nm) |

The DSSP code

The Dictionary of Protein Secondary Structure, in short DSSP, is commonly used to describe the protein secondary structure with single letter codes. The secondary structure is assigned based on hydrogen bonding patterns as those initially proposed by Pauling et al. in 1951 (before any protein structure had ever been experimentally determined). There are eight types of secondary structure that DSSP defines:

- G = 3-turn helix (310 helix). Min length 3 residues.

- H = 4-turn helix (α helix). Min length 4 residues.

- I = 5-turn helix (π helix). Min length 5 residues.

- T = hydrogen bonded turn (3, 4 or 5 turn)

- E = extended strand in parallel and/or anti-parallel β-sheet conformation. Min length 2 residues.

- B = residue in isolated β-bridge (single pair β-sheet hydrogen bond formation)

- S = bend (the only non-hydrogen-bond based assignment).

Amino acid residues which are not in any of the above conformations are assigned as the eighth type 'Coil': often codified as ' ' (space), C (coil) or '-' (dash). The helices (G,H and I) and sheet conformations are all required to have a reasonable length. This means that 2 adjacent residues in the primary structure must form the same hydrogen bonding pattern. If the helix or sheet hydrogen bonding pattern is too short they are designated as T or B, respectively. Other protein secondary structure assignment categories exist (sharp turns, Omega loops etc.), but they are less frequently used.

DSSP H-bond definition

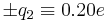

Secondary structure is defined by hydrogen bonding, so the exact definition of a hydrogen bond is critical. The standard H-bond definition for secondary structure is that of DSSP, which is a purely electrostatic model. It assigns charges of  to the carbonyl carbon and oxygen, respectively, and charges of

to the carbonyl carbon and oxygen, respectively, and charges of  to the amide nitrogen and hydrogen, respectively. The electrostatic energy is

to the amide nitrogen and hydrogen, respectively. The electrostatic energy is

According to DSSP, an H-bond exists if and only if  is less than -0.5 kcal/mol. Although the DSSP formula is a relatively crude approximation of the physical H-bond energy, it is generally accepted as a tool for defining secondary structure.

is less than -0.5 kcal/mol. Although the DSSP formula is a relatively crude approximation of the physical H-bond energy, it is generally accepted as a tool for defining secondary structure.

Protein secondary-structure prediction

Predicting protein tertiary structure from only its amino acid sequence is a very challenging problem (see protein structure prediction), but using the simpler secondary structure definitions is more tractable and has been the focus for research for a long time.

Although, the 8-state DSSP code is already a simplification from the continuous variation of hydrogen bonding patterns present in a protein the majority of secondary prediction methods simplify further to the three dominant states: Helix, Sheet and Coil. How the conversion is made from 8- to 3-state varies between methods. Early methods of secondary-structure prediction were based on the helix- or sheet-forming propensities of individual amino acids, sometimes coupled with rules for estimating the free energy of forming secondary structure elements. Such methods were typically ~60% accurate in predicting which of the three states (helix/sheet/coil) a residue adopts. A significant increase in accuracy (to nearly ~80%) was made by exploiting multiple sequence alignment; knowing the full distribution of amino acids that occur at a position (and in its vicinity, typically ~7 residues on either side) throughout evolution provides a much better picture of the structural tendencies near that position. For illustration, a given protein might have a glycine at a given position, which by itself might suggest a random coil there. However, multiple sequence alignment might reveal that helix-favoring amino acids occur at that position (and nearby positions) in 95% of homologous proteins spanning nearly a billion years of evolution. Moreover, by examining the average hydrophobicity at that and nearby positions, the same alignment might also suggest a pattern of residue solvent accessibility consistent with an α-helix. Taken together, these factors would suggest that the glycine of the original protein adopts α-helical structure, rather than random coil. Several types of methods are used to combine all the available data to form a 3-state prediction, including neural networks, hidden Markov models and support vector machines. Modern prediction methods also provide a confidence score for their predictions at every position.

Secondary-structure prediction methods are continuously benchmarked, e.g., in the EVA experiment. Based on ~270 weeks of testing, the most accurate methods at present are PSIPRED, SAM, PORTER, PROF and SABLE. Interestingly, it does not seem to be possible to improve upon these methods by taking a consensus of them . The chief area for improvement appears to be the prediction of β-strands; residues confidently predicted as β-strand are likely to be so, but the methods are apt to overlook some β-strand segments (false negatives). There is likely an upper limit of ~90% prediction accuracy overall, due to the idiosyncrasies of the standard method (DSSP) for assigning secondary-structure classes (helix/strand/coil) to PDB structures, against which the predictions are benchmarked.

Accurate secondary-structure prediction is a key element in the prediction of tertiary structure, in all but the simplest (homology modeling) cases. For example, a confidently predicted pattern of six secondary structure elements βαββαβ is the signature of a ferredoxin fold.

Alignment

Both protein and nucleic acid secondary structures can be used to aid in multiple sequence alignment. These alignments can be made more accurate by the inclusion of secondary structure information in addition to simple sequence information. This is sometimes less useful in RNA because base pairing is much more highly conserved than sequence. Distant relationships between proteins whose primary structures are unalignable can sometimes be found by secondary structure.

See also

- Folding (chemistry)

- protein primary structure

- protein tertiary structure

- protein quaternary structure

- translation

- structural motif

References

- ^ Richards F. M., Kundrot C. E. (1988). "Identification of structural motifs from protein coordinate data: secondary structure and first-level supersecondary structure". Proteins 3 (2): 71–84. doi:10.1002/prot.340030202. PMID 3399495.

- ^ Kabsch W., Sander C. (1983). "Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features". Biopolymers 22 (12): 2577–2637. doi:10.1002/bip.360221211. PMID 6667333.[1]

- ^ Frishman D., Argos P. (1995). "Knowledge-based protein secondary structure assignment". Proteins 23 (4): 566–579. doi:10.1002/prot.340230412. PMID 8749853.

- ^ [|Steven Bottomley] (2004). "Interactive Protein Structure Tutorial". http://www.biomed.curtin.edu.au/biochem/tutorials/prottute/helices.htm. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

Further reading

- C Branden and J Tooze (1999). Introduction to Protein Structure 2nd ed. Garland Publishing: New York, NY.

- M. Zuker "Computer prediction of RNA structure", Methods in Enzymology, 180:262-88 (1989). (The classic paper on dynamic programming algorithms to predict RNA secondary structure.)

- L. Pauling and R.B Corey. Configurations of polypeptide chains with favored orientations of the polypeptide around single bonds: Two pleated sheets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Wash., 37:729-740 (1951). (The original beta-sheet conformation article.)

- L. Pauling, R.B. Corey and H.R. Branson. Two hydrogen-bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Wash., 37:205-211 (1951). (alpha- and pi-helix conformations, since they predicted that

helices would not be possible.)

helices would not be possible.)

External links

- NetSurfP - Secondary Structure and Surface Accessibility predictor

- PROF

- Jpred

- PSIPRED

- DSSP

- WhatIf

- Mfold

- STRIDE

- PSSpred A multiple neural network training program for protein secondary strucure prediction

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

![E = q_{1} q_{2}

\left[ \frac{1}{r_{ON}} %2B \frac{1}{r_{CH}} - \frac{1}{r_{OH}} - \frac{1}{r_{CN}} \right] \cdot 332 \ \mathrm{kcal/mol}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d4d8caa175413871b125384dbe23c50c.png)